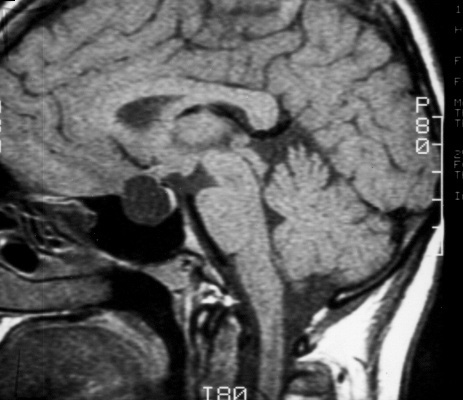

From Lewis Blevins, MD – Pituitary embryology is fascinating. An extension goes down from the brain forming the pituitary stalk and the posterior pituitary. A flat piece of tissue grows up from the upper portions of the mouth and nose, folds over on itself, and then forms the anterior pituitary gland. Those cells in that tissue start to grow to fill out the gland, and, under the regulation of a number of different genes, form anterior pituitary cells of different lineages. The space where it had folded on itself is usually obliterated or scarred down. Sometimes, this area, which is usually at the posterior and anterior pituitary interface, can be seen on cut sections of the pituitary using the microscope; this cleft- like and is called Rathke’s cleft.

Perhaps the most common abnormality of this area is what is known as a pars intermedia cyst. This happens when the cleft opens up, or maybe never even closes, and a little tiny cystic structure forms. These usually measure less than 3 mm in size and are of no consequence. They are seen with regularity on pituitary MRIs if one actually looks for them. In my career, after following a number of these, I have never seen one increase in size or become worrisome in any other way.

Rathke’s cleft cysts are usually a little larger. Anything over 3 mm, in my mind, is a potential Rathke’s cleft cyst. They vary in size from several millimeters to several centimeters. They are, basically, similar to self-filling water balloons. They can increase in size as the cells lining the cyst produce more fluid. Some increase in size rather quickly while others take a very long time. They can be located within the sella turcica, along the pituitary stalk, and even at the base of the hypothalamus. They definitely can cause headaches. Some patients have pituitary dysfunction of varying degrees. However, it is rather unusual to see profound hypopituitarism. In fact, when we see marked hypopituitarism in association with a Rathke’s cyst we worry about one of two things: an infected cyst or granulomatous hypophysitis that may develop when a Rathke’s cyst ruptures it’s fluid into the anterior pituitary gland. Both of these have characteristic radiographic changes.

Generally, I recommend surgery for Rathke’s cysts that are greater than 1 cm in size and/or associated with any degree of hypopituitarism. Additionally, cysts that are smaller but associated with headaches are usually treated surgically. Patient preference also counts.

Surgery involves incising the cyst, draining its contents, and sometimes killing off the lining cells with alcohol or hydrogen peroxide. Sometimes, the lining can be stripped and removed. Unfortunately, however, occasional patients have cyst lining cells that are left behind or somehow survive the operation. These can grow over time and form additional cysts. The overall recurrence rate for a Rathke’s cleft cyst is about 8%. Most recurrences are apparent within 2 to 5 years of follow up. Those with infected cysts, or cysts that contain white material, whether or not infection is proved, have a recurrence rate of about 40%. The recurrence rate in those with presumed infected cysts can be lowered to about 12% in patients treated with six weeks of antibiotics. It is important to know that the use of peroxide or alcohol in the pituitary fossa might result in postoperative hyponatremia occurring within 5 to 7 days after surgery. Symptoms include severe headache and flulike symptoms.

Occasionally, a pituitary cyst is truly a simple arachnoid cyst. These develop when a piece of the arachnoid membranes above the pituitary closes over on itself and forms a CSF-filled water balloon-like structure. They can affect the pituitary. If necessary, surgery is usually performed to open up the cyst so that the fluid flows out of it freely back into the cerebrospinal fluid circulation.

Some pituitary tumors undergo hemorrhage and necrosis (rot) and the dead tissues liquefy forming a cystic area within the tumor. Sometimes, most of the tumor is cystic but, more commonly, significant amounts of solid viable tumor tissue remain. These lesions are approached in a standard fashion depending on tumor subtype. Sometimes, the necrotic debris is removed by the body and the cystic area collapses over time whereas, in other cases, they increase in size necessitating surgery if follow up without intervention had been selected as the course of action.

Epidermoid cysts are rare. Sometimes, these are located in the sella but they are usually located in the area above the sella. They are, basically, cysts formed by skin cells trapped in the region during embryological development. They are often associated with inflammation. Hypopituitarism is common. The cyst contents can leak into the spinal fluid space causing a sterile meningitis. They can be difficult to cure surgically.

Of course, the greatest mimic of the pituitary cyst is the empty sella. I have seen a number of patients thought to have a pituitary cyst but they had a straightforward empty sella.

© 2014, Pituitary World News. All rights reserved.